Breeding program

The Prakochabaan Foundation has undertaken many projects to ensure that Asian elephants have a sustainable future. The history and culture of the elephants in Thailand is vital to understanding why and how our elephants are here.

The PraKochabaan Foundation is dedicated to ensuring there will be elephants for future generations to see and appreciate. Happy healthy elephants breed and the incredible success of our breeding program has a significant impact on the endangered Asian elephant numbers. Check out all our births below!

The Royal Elephant Kraal Village is committed to breeding as many babies as possible. There have been 89 successful births since 2000 – with more on the way. In the nursery right now, we have mothers and their babies that you can play with and care for. If you haven’t seen a baby elephant you will fall in love when you do. By actually spending time with them you will discover how individual they are. They form their own personalities very quickly and it is fun and fascinating watching them play together whilst their mothers try to keep them in line.

Only with more births than deaths can we ensure the survival of the species.

Most recent births 2024

Birth No. 87 and 88 – 7 June 2024

TWINS!

The most exciting birth of all. The biggest reward we could ever have was the birth of the only male and female twins in the world!

It was the biggest surprise ever when Jumjuree popped out another baby at 9.18 pm, after the first baby arrived at 9pm. Everyone was ecstatic! Jumjuree tried to kill the second baby but the mahouts acted quickly and got baby away with no regard for their own safety. Their dedication, commitment and bravery is everything.

History

Phaniat, the place where the elephants are kept and the kings are crowned…

(Jeremias Van Vliet, 1692)

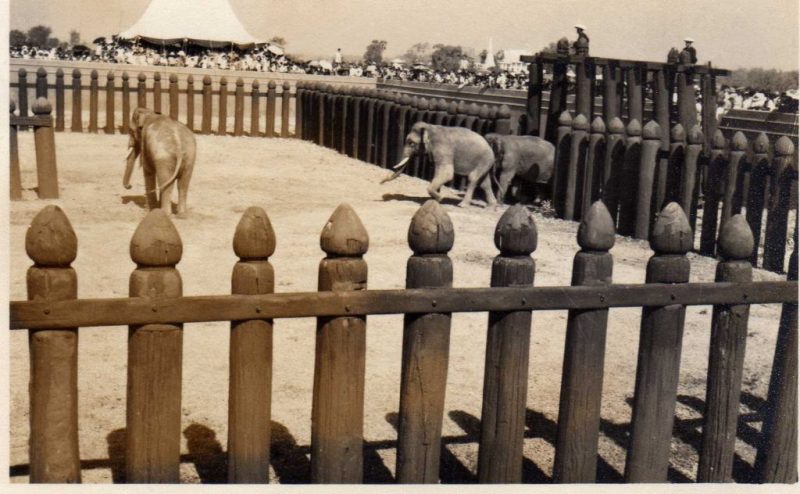

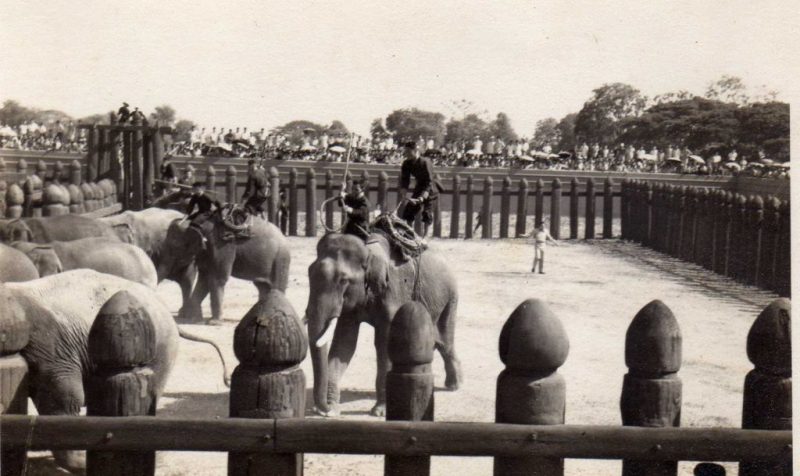

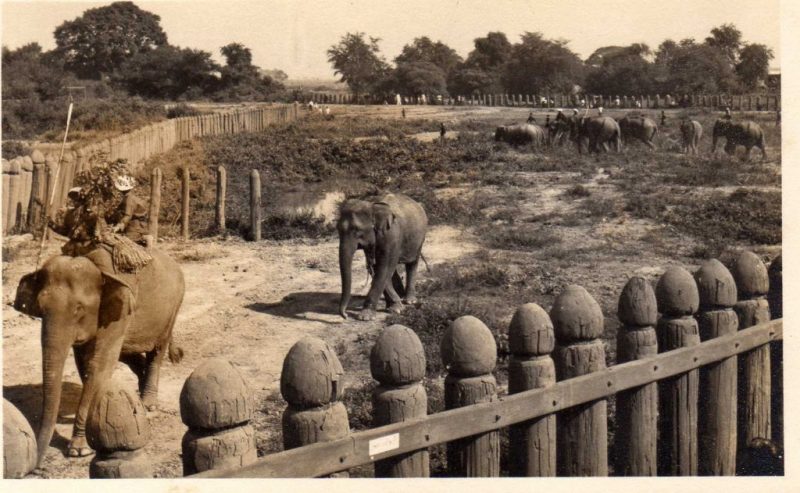

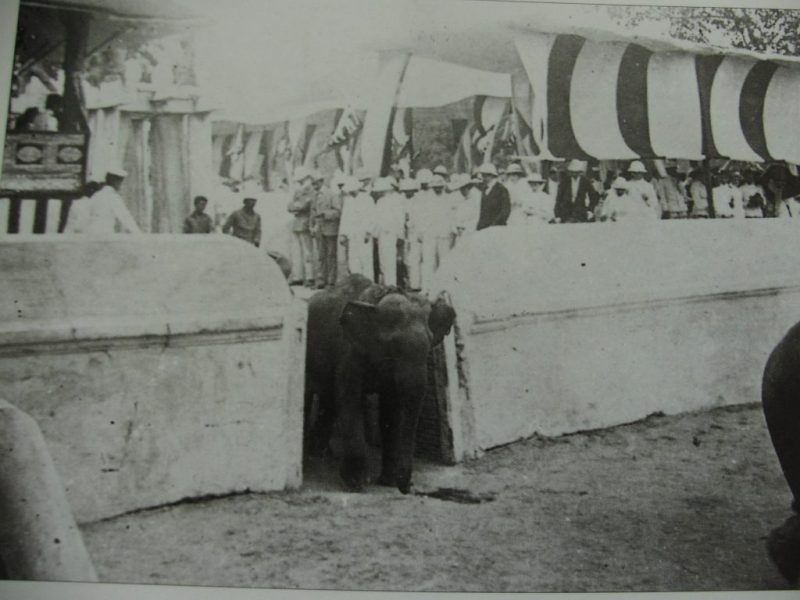

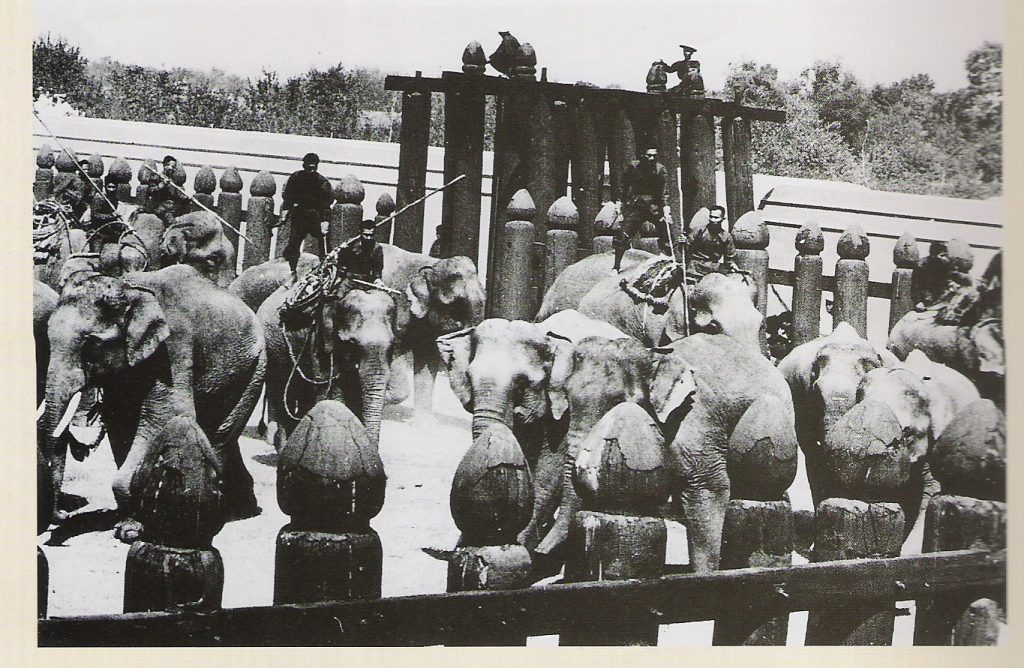

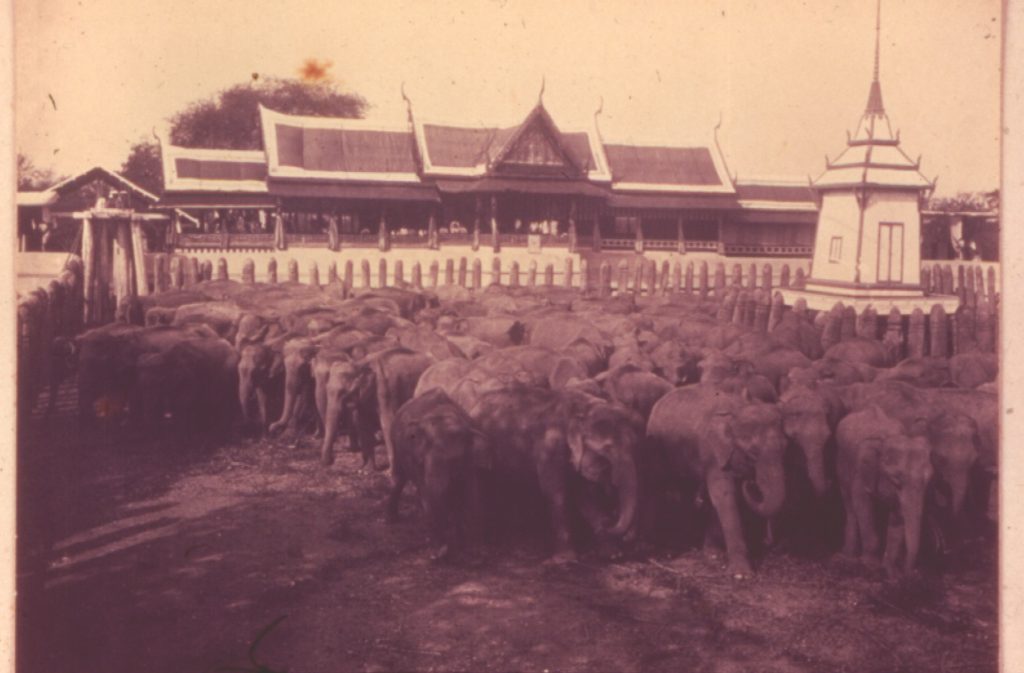

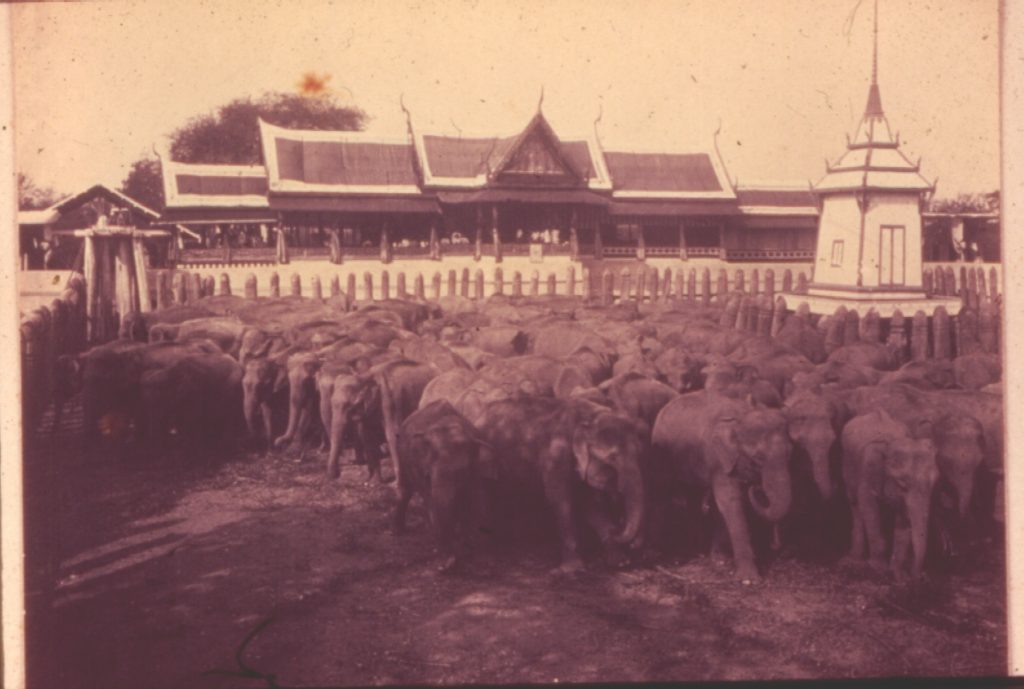

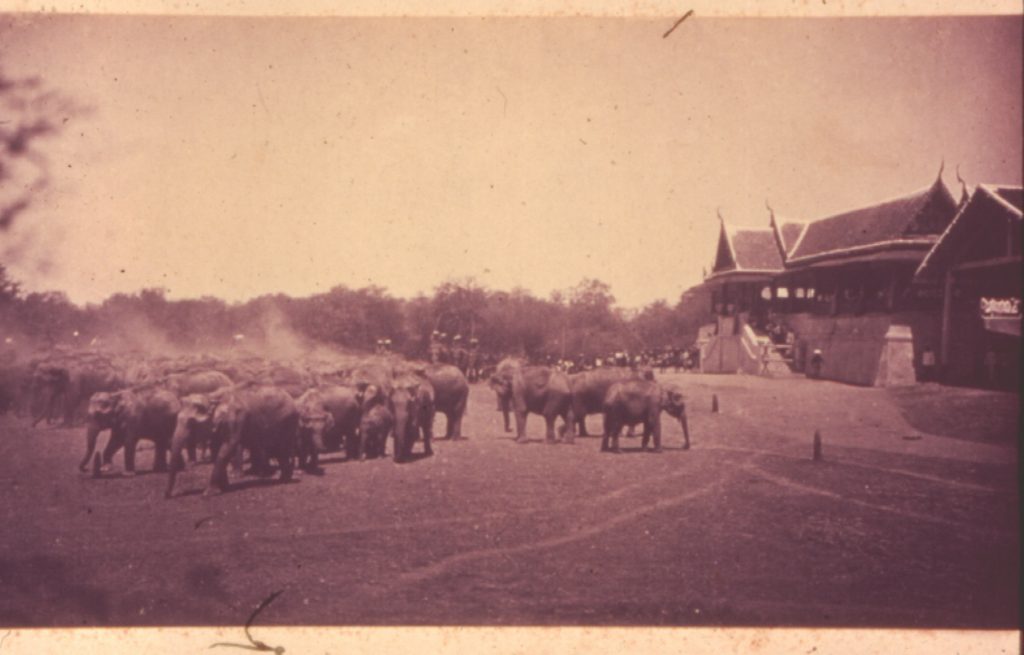

The Royal Elephant Kraal Village is steeped in elephant history. In earlier times it was known as Thamle Ya or the “grass locality”. The last annual round up from the wild was in 1906. A spectacular display, the round up was a testament to the King’s power and the skills of the mahouts. The Royal Elephant Kraal is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the only one left in Thailand. Click through these photos for a fascinating look at Elephant culture of the past.

The outlook from the Ko Jawet Maha Prasat pavilion, from where the kings watched the elephant trapping ceremony, is a large enclosure surrounded with logs having; from the front centre, fencing lines of 45 degrees spread out to both sides far away into the former jungle area. The kraal dates back to the 16th century, when King Maha Thammaracha (r.1569-1590) after the first fall of Ayutthaya in 1569, moved the old elephant kraal near Wat Song to the present site; a time when elephants were not only caught and trained for work and transport, but also used for warfare.

Many visitors in the late 19th and early 20th century had the occasion to visit the kraal in Ayutthaya. George Bacon, visiting Siam in 1857 describes the site as follows:

“After visiting the ruins, therefore, we inspected the kraal or stockade, in which

the elephants are captured. This was a large quadrangular piece of ground, enclosed by a wall about six feet in thickness, having an entrance on one side through which the elephants are made to enter the enclosure. Inside the wall is a fence of strong teak stakes driven into the ground a few inches apart. In the centre is a small house erected on poles and strongly surrounded with stakes, wherein some men are stationed for the purpose of securing the animals. …Once a year, a large number is collected together in the enclosure, and as many as are wanted of those possessing the points which the Siamese consider beautiful are captured. …On this occasion the king and a large concourse of nobles assemble together to witness the proceedings; they occupy a large platform on one side of the enclosure.” [1]

The restoration of Ayutthaya’s ancient kraal, the elephant-trapping pen, began in October 2007. All 980 ageing logs in the fence surrounding the enclosure were replaced. The “sao talung” are the major component of the pen, or “Phaniat Klong Chang”, which wild elephants were driven into for elephant-trapping ceremonies in the Ayutthaya period. All the old timber was replaced under a 16 million Baht restoration project, which was launched to mark King Rama IX’s 80th birthday in December 2007. The governor presided over the ceremony, in which the first of the logs were uprooted from the ground. There was a ritual to obtain permission from the deities before the restoration began, as the kraal is traditionally a sacred place.

Thank you to Ayutthay-history.com. For more information please visit http://www.ayutthaya-history.com/Historical_Sites_ElephantKraal.html

Peter Anthony Thompson somehow fifty years later in 1905, sketches the following picture of the kraal:

“Beyond the busy lines of floating houses, on a tongue of land between two of the numerous branches of the river, stands the paniet or elephant stockade. This is square enclosure of posts, ten feet high and about two feet apart. It is surrounded by a broad wall with a parapet, and at one end is a pavilion for the King and his court. On opposite sides of the stockade are two narrow openings, connected with passages which lead through the wall. These passages are closed by great beams which hang pivoted at one extremity from a frame-work overhead. They can easily be drawn aside by ropes, and when the tension is relaxed they swing back again, and bar the entrance. Outside the wall more posts are planted, so as to enclose a large triangular space, whose apex is at the narrow gap in the wall. In the base of the triangle a wide gate is left, and beyond this radiating lines of posts direct the advance of the elephants. This is the scene of the great “Elephant Hunt,” which takes place once in every three or four years.” [1]

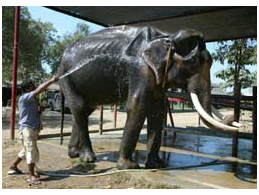

Rescue and Rehabilitation

The Prakochabaan Foundation has rescued many bulls from terrible circumstances, It is one of our main missions to take care of sick, abused, injured and killer bull elephants and rehabilitate them.

Killer elephant saved from death

On 21 August 2007, Pang BoonSeuhm aged 68 came to the Royal Elephant Kraal Village just days after she killed a man. BoonSeuhm remembered the man in question who had taunted her 10 years ago with firecrackers and withholding food. The same man came back and taunted her again and she killed him.

She was to be shot as the owner could no longer keep her. Previously he had decided that he did not want to sell her to a nearby rubber plantation to work, due to her age. BoonSeuhm’s owner heard about our program to retire old elephants and how the Kraal had retrained killer elephants in the past and given them a new life. This was a happy alternative for him, BoonSeuhm and us here at the Kraal. BoonSeuhm can now be assured of a happy caring retirement

Wild elephant rescue

A team of expert mahouts go to Khun Song to assist with hoisting an injured elephant out of the mud wallow he created when he collapsed and could not get up. It is thought the bull elephant was about 50 years old and had been attacked by another bull. Our mahouts managed to get him to rise enough to get a harness under him so he could be lifted by a back hoe. Tragically he ended up succumbing to his injuries.

This wild elephant was found caught in a poachers snare. Due to the horrific extent of its injuries, it was estimated it had been suffering with this snare for about one month. It was caught up and taken to the Kraal where intensive care was provided for six months. Tragically due to the horrendous extent of its injury and the associated problems of infection and the damage that had created the elephant did not survive. (See article: AEACP Obituary: Plai Tong Pa Boom for more information)

Research Papers

“These studies could not have been conducted without generous assistance from Kh. Sompast Meepan. He provided advice on bull behavior, as well as giving guidance to mahouts on elephant handling for sampling, particularly when bulls were in musth. Access to Kh. Sompast’s uniquely large population of tractable adult bulls, along with the participation of well-trained & extremely supportive mahouts, in combination with Kh. Sompast’s vast knowledge of elephant behavior, enabled this work to take place.” Lisa Yon

“A longitudinal study of LH, gonadal and adrenal steroids in four intact Asian bull elephants (Elephas maximus) and one castrate African bull (Loxodonta africana) during musth and non-musth periods”

During musth, a number of hormones in the body are increased. Until now, the only hormones studied have been the male sex hormones, testosterone, androstenedione and dihydrotestosterone. All of these hormones are produced by the testes in the bull elephant.

Musth can be seen as a very stressful time for a bull elephant. Bulls in musth decrease their food intake, greatly increase their territories (so they roam over a much larger range), fight more with other elephants (and with other species), and at the height of musth they lose large amounts of water to urine dribbling (they become ‘incontinent’ and dribble urine almost constantly; this is probably to leave specific chemicals behind to communicate their state to other elephants). The adrenal glands are involved in the stress response in most species studied to date, and it is reasonable to think that they would be active during the stressful time of musth.

The adrenal glands produce the hormone cortisol in times of stress, but they can also produce some sex hormones, including testosterone, androstenedione and the weaker male sex hormones (androgens) androstenediol and DHEA. These last two hormones are produced in large part by the adrenal glands, not by the testes. The purpose of this study was to determine if the adrenal glands increase their hormone production during musth. Weekly blood samples were taken from two adult Asian bull elephants at the Ayutthaya Elephant Palace and Royal Kraal, and from two Asian bull elephants at the Oregon Zoo in the United States over a period of 11-15 months, during musth and non-musth periods. Samples were measured for levels of cortisol, testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, DHEA, androstenedione and androstenediol. In three of the four bulls, all of the hormones studied increased during musth, including those mostly produced by the adrenal glands. This suggests that the adrenal glands are actively producing hormones during musth in the Asian bull elephant. The significance of this adrenal hormone production is unknown.

This study was conducted to further explore the role of the adrenal glands in musth. The classical pathway for activating the adrenal glands in times of stress involves production and release of the hormone ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) from the pituitary gland in the brain. This hormone then stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol (a stress hormone), as well as some sex steroids (as mentioned above).

Synthetic ACTH was given to four adult Asian bull elephants at the Ayutthaya Elephant Palace and Royal Kraal. Blood samples were taken and measured for levels of cortisol and the male sex hormones (androgens) mentioned above (testosterone, androstenedione, androstenediol, and DHEA). Cortisol increased as expected in response to ACTH. The response of the androgens to the ACTH was quite different from the pattern seen during musth: DHEA doubled, androstenedione and androstenediol showed no consistent pattern of response, and testosterone actually decreased in all the bulls. During musth, by contrast, all of these hormones increased (testosterone markedly so). This pattern of results suggests that the classical adrenal gland activation pathway, which is triggered by stress, is not the route which is stimulating hormone production by the adrenal glands during musth.

Lecturer in Zoo and Wildlife Medicine

School of Veterinary Medicine and Science University of Nottingham,

Sutton Bonington

Head of Research, Twycross Zoo – East Midlands Zoological Society

University of Nottingham : Twycross Zoo:

Tel: +44 (0) 115 951 6358 Tel: +44 (0) 182 788 3136

Fax: +44 (0) 115 951 6440

Email: lisa.yon@nottingham.ac.uk Email: lisa.yon@twycrosszoo.org

Assessment of Pregnancy Status of Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus) by Measurement of Progestagen and Glucocorticoid and Their Metabolite Concentrations in Serum and Feces, Using Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA)

The study was to find patterns of progestagen (progesterone and its metabolite) and glucocorticoid and their metabolite concentrations in serum and feces of pregnant Asian elephants (Elephas maximus). The 5 female Asian domestic elephants were naturally mated until pregnancy. After that, blood and feces samples were collected monthly during pregnancy for progestagen, glucocorticoid and their metabolites analysis by enzyme immunoassay (EIA). The results showed the serum progestagen concentration during gestation was 2.11 ± 0.60 to 18.44 ± 2.28 ng/ml. Overall, serum progestagen concentration rose from the 1st month to reach peak in the 11th month, after which it declined to its lowest level in the 22nd month of pregnancy. Fecal progestagen concentration varied from 1.18 ± 0.54 to 3.35 ± 0.45 µg/g during pregnancy. In general, fecal progestagen concentration increased from the 1st month to its highest level in the 12th month. After this, it declined reaching its lowest point in the 22nd month of pregnancy. Glucocorticoid hormones and their metabolite concentrations both in serum and feces fluctuated from low to medium throughout almost the entire pregnancy period and then rapidly increased around the last week before calving. Our study suggests that this profile of progestagen and glucocorticoid hormones and their metabolite concentration levels in serum and feces can be used to assess the pregnancy status of Asian elephants. If serum and fecal progestagen concentrations were found in very low levels and glucocorticoid and their metabolite concentrations were found in very high levels, it was indicated that the cow elephant would calve within 7 days.

“Study area and experiment animals: This study was conducted on 5 pregnant Asian elephants which were domesticated in a semi-captive condition in the Ayuttaya Elephant Palace camp in Pranakornsri-Ayuttaya province, Thailand. All elephants in this study were chosen randomly from a mixed group. They varied in age between 21 and 37 years, had no reproductive problems and had not calved for at least 3 years previously. The animals were habituated to humans and used for tourist treks outside of the camp in the early morning or late afternoon. They were brought back to the camp for forage and supplementary feeding each evening. During their working period, they were given a variety of foods, such as banana, sugar cane and hay from tourists. In addition, they had access during this time to water ad libitum and natural grass. In camp, the elephants were divided into different groups according to age (calves, sub-adult, adult and old adult). The cows were separated from the bulls except during the breeding period. During this time, the bulls were walked to detect estrus for 30 to 60 min, 3 to 5 times per week in the early morning. When the cows were found to be in standing heat, they were allowed to mate until, they refused mounting. Pregnancy diagnosis was determined monthly by transrectal (linear transducer; 5.0 to 12.0 MHz) and transabdominal (convex transducer; 2.0 to 8.0 MHz) ultrasonography scanning (Model Medison portable ultrasound machine; Version SonoAce R3, Samsung Medison Co., Ltd., California, U.S.A.) between the 2nd and the 4th month after the last mating. Under their general management schedule, the elephants were dewormed and looked after by a veterinarian from the elephant camp. These experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Mahanakorn University of Technology, Nong-chok, Bangkok, Thailand (Project: VET-MUT008/2553).